The Economist (19-06-2014)

IF YOU’VE been on Facebook recently, and you’re the kind of person who reads this column, there’s a good chance you’ve seen one of two viral language tests going round. Like many things on Facebook, they’re a fun diversion. Unlike many things on Facebook, they’re helping serious researchers learn about language and the mind.

The first is called “Which English?”, from the website Games With Words. Like another recent popular dialect quiz, it attempts to guess where you might have learned most of your English. But the version going round last year focused only on American dialects, and mainly asked questions about vocabulary and pronunciation. Which English? asks grammar-focused questions instead. It is also international: it will not only rank three guesses for the English dialect that has influenced you the most. It will also give three guesses as to your native language. Joshua Hartshorne, the MIT researcher behind the Games With Words lab that created the quiz, says that the top three guesses included the correct one about 80-90% of the time. Anecdotally, Johnson’s Facebook friends find it either eerily accurate or amusingly inaccurate. (It nailed your columnist’s own home dialect.)

What’s interesting is what’s going on behind the scenes. Mr Hartshorne, a cognitive scientist, conceived Which English? to research not dialect but language acquisition, and in particular the “critical period” hypothesis. Many linguists believe that there is a period for language learning (just before puberty) after which it becomes much harder to learn a foreign language.

Mr Hartshorne was not sure. The critical period may apply to the acquisition of a native-like accent, he thinks. But it may not apply to grammar. A previous study has suggested that grammar-learning ability falls off smoothly (not suddenly, after the critical period) depending on the age at which the learner begins learning. The earlier study relied on self-reporting, so he set out to find out what he could by actually testing people’s grammar, and then asking a few basic demographic questions. With around 500,000 test-takers so far, his results should be statistically robust, though he has gotten fewer non-Anglophone immigrants to Anglophone countries than he would like. (So do take the quiz, especially if you belong in that category.)

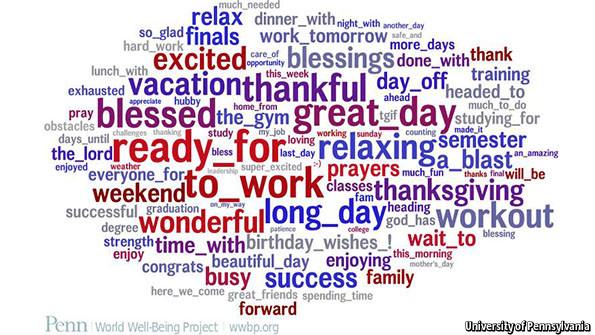

The second “language test” going around social networks uses language as a predictor of personality. Last year, researchers published a study in PLoS One, an online journal, in which 75,000 volunteers allowed their Facebook postings to be analysed, and also took a personality test on the “big five” personality traits: agreeableness, conscientiousness, openness, extraversion and neuroticism. Rather than hypothesise words or phrases that would predict personality traits, the researchers let the data speak for themselves, seeing which words emerged most typically with which traits. The word-clouds emerging from the study, for low and high values of each of the five criteria, are fascinating. Disagreeable people swear, introverts like anime, conscientious people invoke prayer and blessings (their word-cloud is pictured above), and those less “open” (ie, those who are unalytical and unreflective) are more likely to use internet-shortenings (UR, 2day, any_1) and omit punctuation (dont, wont).

One of the researchers works for a Berkeley-based company called Five, which has opened its version of the same tool to the public. If you give Five permission to scour your Facebook feed, it will not only guess the results you would get from a personality test, but will also score your friends, based on the text that appears in your feed, and show which friends you are most similar to. 175m personalities have been analysed so far.

The results are visually well designed and absorbing. Johnson was dismayed, upon first seeing his results, to find himself a world-class curmudgeon, with a 12% score on agreeableness. This was the result of only a few postings of mine, scooped from The Economist’s digital editor’s own Facebook feed. A fuller study of my own feed bumped my score up to a still-sour 36% on agreeableness. Both times round Johnson scored highly on Openness—87%. But while open to the world, your columnist is apparently often unamused by what he finds.

Or perhaps not. Two other online tests scored Johnson’s personality clearly differently from Five’s prediction (and found me a lot more agreeable). Interestingly, in Five’s analysis, my “most similar” friends were nearly all journalists, many of them delightful people who also got low scores for “agreeableness”.

Johnson asked on Facebook whether they felt they were their unique selves on Facebook. Many reported that they have topics they avoid completely on the social network, whether their kids or politics. Others said that they had a bit of a Facebook mask, whether funny or sardonic. Johnson’s “most similar” friend is a cartoonist with a wicked wit with pen in hand; she is also an utter sweetheart in person.

Five is not delivering a personality test, but guessing the results you would get from a personality test based on your Facebook scribblings. So (conscious or unconscious) Facebook “masks” will skew the results. Nikita Bier, one of Five’s co-founders, acknowledges the challenge, but says that the huge source of data that Facebook offers could refine the model over time. And, he says, a suitably designed machine-learning model might even be trained on a single person’s writing to learn to detect, for example, sarcasm.

Making a fun online game out of a serious bit of research is an ingenious way to drive up participation and potentially solve the kinds of statistical problems that bedevil smaller studies. They will, of course, mostly reach “WEIRD” subjects, ie, Western, Educated, from Industrialised Rich Democracies. But as more of the world goes online, “Western” in the acronym might be simply replaced by “wired”, giving researchers access to an ever-more-diverse slice of humanity.

In a potential downside, what if all this could be used against us? Some countries have already felt the need to enact legislation preventing potential employers from snooping on employees on Facebook. What if they administered a Five-style “personality test” (not really a test at all, but a prediction) to those they were looking into? Your disagreeable columnist had better not quit his day job. It’s another lesson in the need for modern people to guard their privacy carefully—and so yet one more reason they might well adopt a “Facebook mask”.