IS BARACK Obama a narcissist? Charles Krauthammer thinks so, and he should know.

The conservative American pundit is a psychiatrist by training, and with his Vulcan-like facial features, gravelly voice and articulate defence of conservative positions, he presents himself as an intellectual cut above most of the shouting heads in Washington.

But Mr Krauthammer has repeatedly flogged a claim that first a linguist, then a comedian, and finally the junk-plus-real-news website Buzzfeed have shown to be utterly false. The claim is straightforward: that the American president uses words like “I”, “me”, “my” and “mine” so often he must have a clinical level of self-love. “For God’s sake, he talks like the emperor Napoleon,” says Mr Krauthammer.

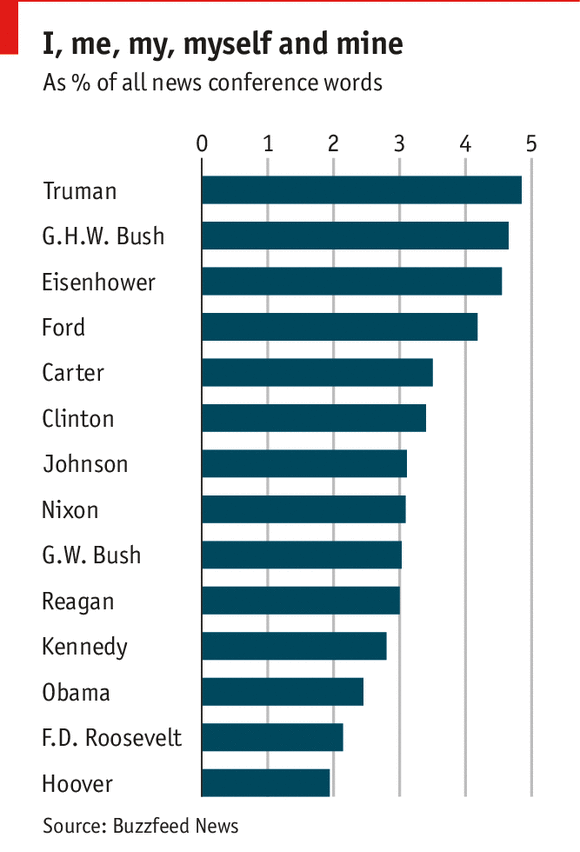

The claim has been made by other conservative pundits, such as George Will. So Mark Liberman, a linguist at the University of Pennsylvania and the keeper of Language Log, a group language blog, began doing what none of them did. He counted. “I” is the most common word in English speech—but Mr Obama uses first-person singular pronouns less than all of his recent predecessors.

Figuring this out doesn’t require Ph.D. in linguistics, just a calculator. Mr Liberman began debunking the myth in 2009. Johnson wrote about it in 2011. Even Steven Colbert, who pretends to be a conservative pundit for laughs, showed last month that Mr Krauthammer used “I” three times more in his radio interview than Mr Obama did in the “narcissistic” speech Mr Krauthammer offered as evidence.

But never mind the facts; the myth seems unkillable. Neither the analysis of a great scientific populariser (Mr Liberman) nor reach of Buzzfeed (130m monthly users) nor the sting of satire (of which Mr Colbert is a virtuoso) can defeat confirmation bias. Mr Krauthammer and a host of others “know” that Mr Obama is a narcissist. Every time he utters an “I” proves it to be so.

Some people will always refuse to check their favorite facts. But what do the actual facts tell us? It is hard to say, because merely totting up I/my/me/mine words offers no easy conclusions. Who is the biggest user of “I” and such since 1945? Why, the colossal egotist Harry Truman, of course, followed by three Republicans, none of whom were known for arrogance: the first George Bush, Dwight Eisenhower and Gerald Ford. Those leftists who saw George W. Bush as a swaggering cowboy should take note that he is near the back of the pack in I/my/me/mine terms, just a bit ahead of Mr Obama.

Can pronouns tell us nothing? One study cited by Mr Liberman shows no link at all between pronoun use and clinical narcissism. But James Pennebaker, a psychologist at the University of Texas, has shown that “I” usage does indeed correlate with certain attributes—but these include depression and low status, not arrogance and high status. The presidency of the United States is not a particularly low-status job. So perhaps Mr Krauthammer would like to remotely diagnose Mr Obama with depression.

Questions of language are not just questions of style; quite often they are questions of fact. The good news is that through the internet more linguistic facts are available to amateurs than ever before. The world wide web itself is a huge body of language, and so a fascinating place to do linguistic research. Google’s free “Ngram viewer” shows the rise and fall of words and phrases in books over time. While free word-cloud software easily turns speeches into arresting visuals highlighting prominent words.

The bad news is that the more data and quick-and-dirty tools are available, the more pundits will be tempted to “prove” something with a lazy count, devoid of serious argument. One paper examined a list of “individualistic” words, and found them increasing in American books (through Google’s Ngram tool). The study was quickly touted as proof that Americans had become more self-centred. But words like “individual” and “sole” actually declined in usage, while many “communal” words increased alongside “individual” words, with little recent change in the overall individual-to-community ratio. This invites the possibility that those who built the study had simply chosen trendy words. In any case, any such result requires analysis before being spread far and wide. It is far from obvious that high-status people avoid first-person pronouns, as Mr Pennebaker found, for example.

More data means more bad analysis, including language analysis. No one should be discouraged from doing their own fact-based research on language. Johnson is a big believer that language discussions need more facts and fewer opinions, and revels in fun facts. But for fun facts to be facts (take note, Mr Krauthammer), they must be true. And for them to be fun, they must illuminate, rather than confuse or misdirect.